The Influence of Chinese Calligraphy on Modern Art

Chinese calligraphy, an art form revered for millennia, is far more than just beautiful writing. It is a profound expression of culture, philosophy, and the human spirit, captured through the dance of ink and brush. Its deep roots in Chinese history have nourished not only traditional aesthetics but have also unexpectedly branched out, significantly influencing the course of modern and contemporary art across the globe. As we explore this fascinating connection, we uncover a dynamic dialogue between ancient traditions and modern sensibilities, revealing how the essence of calligraphy continues to resonate and inspire artistic innovation today, in 2025.

Foundations and Early Encounters

The Essence of Calligraphy

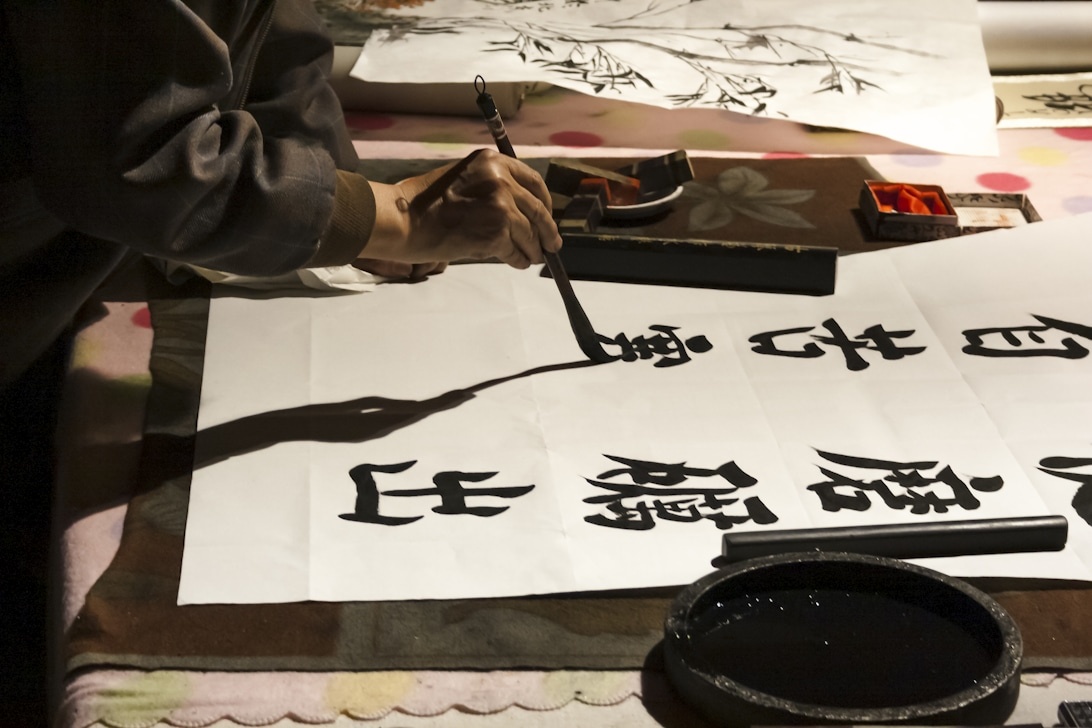

At its core, Chinese calligraphy is the art of the line, prioritizing expressive power over mere legibility. Traditionally considered one of China’s highest art forms, mastery demanded immense discipline, reflecting the artist’s character, knowledge, and inner state – often described as channeling vital energy or ‘Qi’ through the brush. The foundational tools, the ‘Four Treasures of the Study’ (brush, ink, paper, and inkstone), though simple, allow for infinite nuance. The flexible animal hair brush, the ink’s variable consistency achieved by grinding an inkstick on the stone, and the absorbent qualities of Xuan paper all contribute to the unique texture and dynamism of each stroke. The eight basic strokes, like the decisive horizontal ‘héng’ or the delicate ‘diăn’ point, form the building blocks for thousands of characters. Over centuries, diverse scripts evolved, each with a distinct aesthetic: the ancient seal script (zhuànshū), known for its archaic, often pictorial quality; the formal clerical script (lìshū), characterized by simplified, squared forms suitable for official documents; the fluid and abbreviated cursive script (cǎoshū), prized for its expressive freedom; and the clear, standard regular script (kǎishū), which became the basis for printed forms.

Historically, calligraphy was intrinsically linked to the ‘literati’ – the educated scholar-official class who shaped China’s cultural and political landscape. It served as more than art; it was a marker of refinement and social standing, essential for communication and disseminating ideologies, a role detailed on platforms like China Artlover. This deep cultural embedding ensured its persistence. Inscriptions adorned temples, homes, and public spaces, weaving calligraphy into China’s visual environment. Even during the tumultuous 20th century, while bold, block-like characters conveyed revolutionary slogans, traditional brush calligraphy retained its prestige. Leaders like Mao Zedong, himself a calligrapher, practiced and promoted it, demonstrating its enduring cultural weight, a phenomenon explored in studies on calligraphy’s role in modern China. This legacy continues today, visible in art school curricula and the auspicious couplets gracing doorways during festivals.

Influence Spreads Westward

One of the most fascinating chapters in calligraphy’s story is its unexpected influence on Western modern art, particularly during the mid-20th century. Artists associated with Abstract Expressionism in America and Art Informel in Europe discovered profound inspiration in calligraphy’s principles. As highlighted by sources like CSSToday, figures such as Mark Tobey, Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, Antoni Tàpies, Willem de Kooning, and others were captivated by its gestural freedom, the expressive power of the line, and the inherent abstraction within calligraphic forms. Tobey, a pioneer in this integration, developed his ‘white writing’ style directly from studying Asian calligraphy. Franz Kline’s bold, black-and-white canvases powerfully echo the dynamic energy and structural presence of large-scale characters, stripped of literal meaning.

These Western artists recognized calligraphy’s focus on the act of creation – the embodiment of energy (Qi) and emotion in the brush’s physical movement. Calligraphy offered a historical precedent for non-representational art, where process and gesture were paramount. The nuanced textures achievable with ink, the dramatic interplay of black and white, and the rhythm and spontaneity of the strokes provided a rich vocabulary for artists breaking free from traditional Western representation. They adapted calligraphic elements – enlarged brushstrokes, character structures, material textures – to explore new emotional landscapes and abstract concepts. This cross-cultural fertilization, detailed in resources like INKstudio’s exploration of abstraction’s origins, reveals calligraphy’s universal appeal as a language of pure form and gesture, touching artists from Jackson Pollock to Cy Twombly.

Reimagining Heritage Modern Transformations within Chinese Art

While Western artists drew inspiration from afar, artists within China navigated their own complex relationship with this ancient tradition amidst modernization. The 20th century brought challenges: the influx of Western art forms and cultural upheavals disrupting traditional artistic education. This spurred intense debates and diverse approaches as artists sought to reconcile heritage with contemporary realities.

Navigating Tradition and Modernity

Some sought revitalization by delving deeper into tradition. Figures like Zhao Zhiqian and Wu Changshuo, active in the late Qing dynasty, turned to ancient epigraphy and seal carving, infusing their calligraphy and painting with archaic power. Wu Changshuo masterfully applied calligraphic brush techniques to his paintings. Later, artists like Qi Baishi skillfully blended the literati tradition’s sophisticated brushwork with folk art’s directness. Others, like Xu Beihong, advocated adopting Western realism, though often struggled to reconcile its focus on ‘formal likeness’ (xíng sì – exact appearance) with the traditional Chinese emphasis on ‘spirit resonance’ (shén sì – capturing the inner essence or vitality), a core principle prioritizing spirit over photographic accuracy. These diverging paths, explored in discussions like those presented by CAFA Art Info, highlight the dialogue between indigenous traditions and external influences. Artists like Ding Yanyong exemplified this tension, returning to traditional ink styles after studying Western art, finding inspiration in calligraphic spontaneity.

The Modern Calligraphy Debate

Beginning in the mid-1980s, a distinct ‘modern calligraphy’ movement emerged in China, sparking critical debate about its definition and legitimacy. As artists began experimenting radically, questions arose: could works featuring stylized characters, fragmented texts, invented scripts, or purely abstract lines detached from linguistic meaning still be called ‘calligraphy’? This debate, outlined in academic explorations, revealed two main currents. Modernists, represented by figures like Wang Dongling, argued for evolving the tradition by integrating Western abstract elements while retaining a connection to the calligraphic lexicon and brushwork – essentially modernizing from within. In contrast, the avant-garde pushed for a more radical break, sometimes termed ‘anti-calligraphy.’ This approach sought to deconstruct characters entirely (like BAI Qianshen’s unreadable characters or Xu Bing’s invented scripts), focus solely on the abstract beauty of the line, or shift into performance, multimedia, and installation art, aiming for a universally understood artistic language potentially detached from traditional calligraphic constraints.

Contemporary Voices The Brush in Today’s China

Today, contemporary Chinese artists continue this engagement in diverse ways. Many, like Xiao Ping, master both traditional painting and calligraphy, highlighting their symbiotic relationship. Others, like Zhu Wei, use traditional materials like Xuan paper but incorporate contemporary elements, such as large seals bearing website addresses. Artists such as Qiu Deshu experiment with materials themselves, employing his innovative ‘fissuring’ technique – tearing painted Xuan paper mounted on canvas to reveal layers beneath, creating texture and inverting traditional compositions, conceptually linked to seal carving. Figures like Xu Lele strive to revitalize scholar painting aesthetics. Even artists incorporating diverse influences, like Yu Peng or Wei Dong, often express deep reverence for ink painting, calligraphy’s sibling art, lamenting the potential loss of these foundational techniques, as noted in the Williams College Museum of Art collection overview. Xu Bing famously explored language structure with works like ‘Square Word Calligraphy,’ arranging English letters into Chinese character formats, bridging cultures as discussed on platforms like Brewminate. The monumental works of Taiwanese artist Tong Yang-Tze, consciously dialoguing with classical calligraphy and Western abstract painting, exemplify this global conversation, gaining recognition in major institutions like The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Expanding Influence and Enduring Resonance

Beyond Painting Broader Artistic Impact

Calligraphy’s influence extends beyond scrolls and canvases. Its principles permeate other artistic domains and regions. In Southeast Asia, the development of Singapore-Malaysia watercolour art shows a unique fusion of Western techniques with the expressive brushwork and compositional aesthetics of Chinese calligraphy, creating a distinct regional style. Similarly, interactions in South Korea reveal a dynamic process of ‘selection and creation,’ where the tradition is actively reinterpreted, leading to unique developments as suggested by research presented via Atlantis Press. Exhibitions like ‘Dancing with the Qi’ (running February 5 – March 13, 2025) showcase contemporary artists like Cui Fei, Zhen Guo, Sin-ying Ho, Huang Xiang, Xin Song, and Yin Mei who ‘transmediate’ calligraphy’s essence – its energy (Qi), gesture, and mindful presence – across diverse media like ceramics, papercuts, photography, found materials, and performance art. This demonstrates calligraphy’s power to inform various modern practices, asserting its relevance against digital technologies.

The Living Line Today

In an era defined by speed and digital interfaces, calligraphy’s enduring appeal might seem paradoxical. Yet, its emphasis on the human touch, mindful process, and direct expression of energy makes it deeply relevant. The practice demands patience, control, and a mind-body connection, offering a counterpoint to modern life’s disembodiment. Artists like Wang Dongling, a leading figure collected worldwide and featured in collecting guides, explicitly aim to modernize and globalize the art form. He experiments with monumental scale in ‘mad cursive’ performances, creates abstract ink paintings derived from calligraphic gestures, and even explores camera-less ‘photographic calligraphy,’ believing in its potential as an international art form. While debates on authenticity continue, the fundamental power of the calligraphic line – conveying emotion, structuring space, capturing creation – remains undeniable. It serves as a vital link to cultural heritage for many in the diaspora and offers a universal language of form and gesture that continues to inspire artists and captivate viewers globally. The brushstroke’s journey is far from over; it continues tracing new paths, reminding us of the timeless power of human creativity expressed through ink, paper, and the living line.